Vitality in old age

The Aging Gut Flora

The digestive tract supplies our bodies with many nutrients every day. The intestinal flora also plays an important role here. It not only helps in the processing of food but also has a significant influence on the power of the immune system. The defence against harmful inflammation requires an intact interaction of countless metabolic processes in the body, for which the bacteria of the intestinal flora are irreplaceable. Medical research is also discovering more and more connections between the microbial balance in the gut and age-associated health problems.

The dream of eternal life may never come true, but researchers believe that a maximum of about 120 years is possible. This also corresponds to the age of the oldest human being to date: Jeanne Calment, from France, who died in 1997 at the age of 122 years and 164 days. From a medical point of view, the focus is not on the number of years reached, but on the state of health in which old age is experienced. When exactly the natural ageing process begins in humans cannot be determined so precisely. However, doctors, ageing researchers and others essentially agree on one point: from the age of 35, ageing accelerates. What, how and why exactly it happens in the following decades is still unclear. Basically, it can be assumed that a combination of genetic predisposition, e.g., regarding cell ageing, environmental influences, the social environment as well as epigenetic changes influence ageing over the course of life.

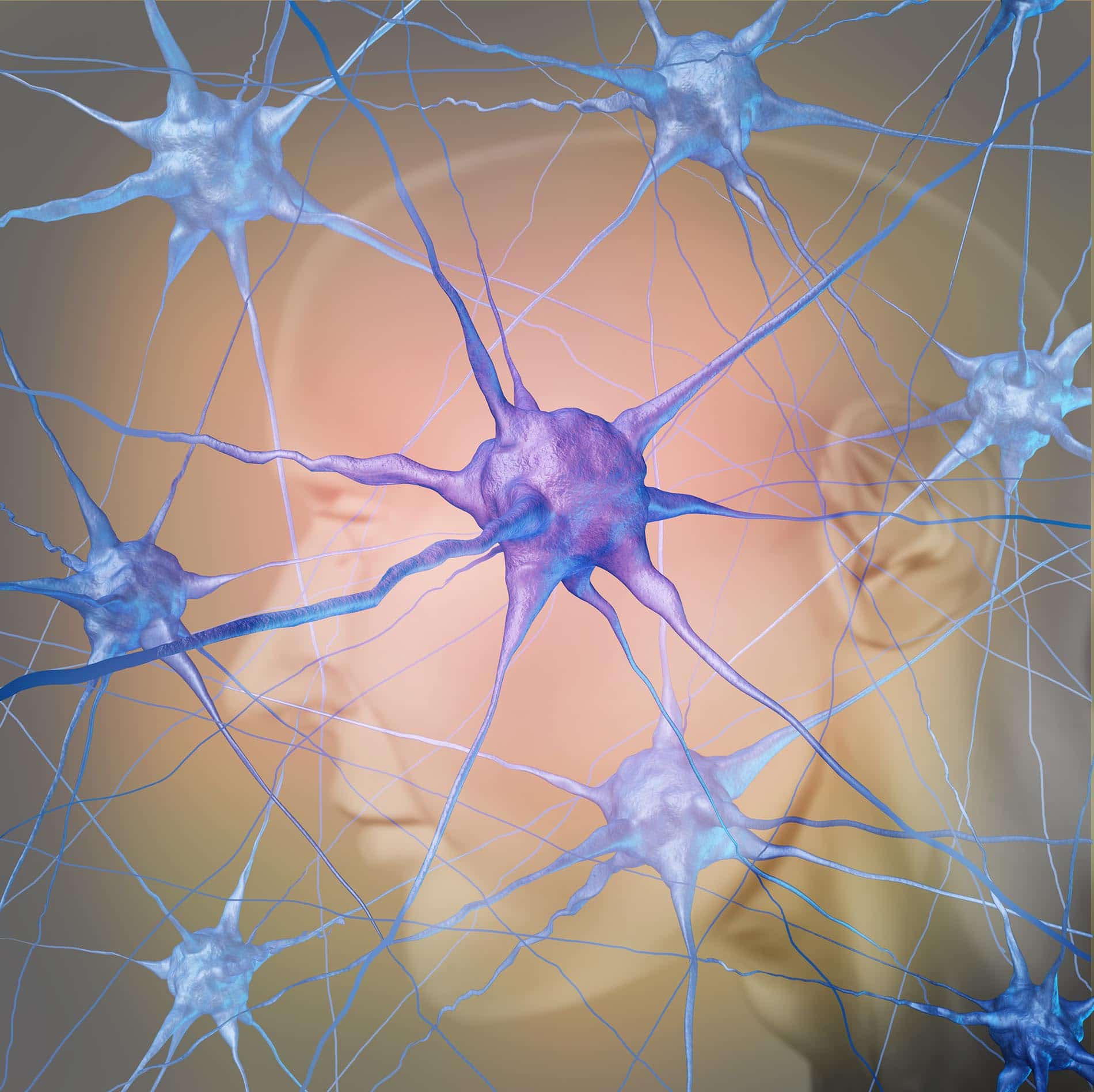

Dementia and the Gut Flora

A major headache for medical research is forgetfulness, or in severe cases, dementia. A real breakthrough in the treatment of these diseases is still lacking. Medical science knows best what preventive measures can prevent or halt this gradual process. Board games, for example, are at the top of the list, as are reading, learning a new language, and dancing.

Evidence that, among other things, the intestinal flora, the microbiome, plays a role in dementia-related degradation processes in the brain is appearing more and more frequently in the scientific literature. Austrian physicians such as Prof. Dr. Friedrich Leblhuber are at the forefront of research.

Prof. Leblhuber works as a specialist in neurology and psychiatry in Linz and is focused particularly on neuropathological processes. "The developments in microbiome research are fascinating," he says in an interview with "bauchgefühl" magazine, referring among other things to the results of a scientific study published in the renowned scientific journal "Neural Transmission". This joint study by staff from the Landesnervenklinik Linz, the Medical University of Innsbruck, and the Biovis Institute in Limburg in Germany analysed inflammatory markers in patients with dementia.

Leaky Gut

How does it work? Highly specialised laboratory methods and genetic engineering procedures make this possible, e.g., by analysing patients' stool samples. Among other things, so-called inflammation markers can be identified. They provide information on whether and to what extent inflammatory but symptomless processes are taking place in the body. Prof. Leblhuber and his colleagues examined these parameters in patients with dementia because there are now numerous indications of a connection between infections and the degradation processes in the brain.

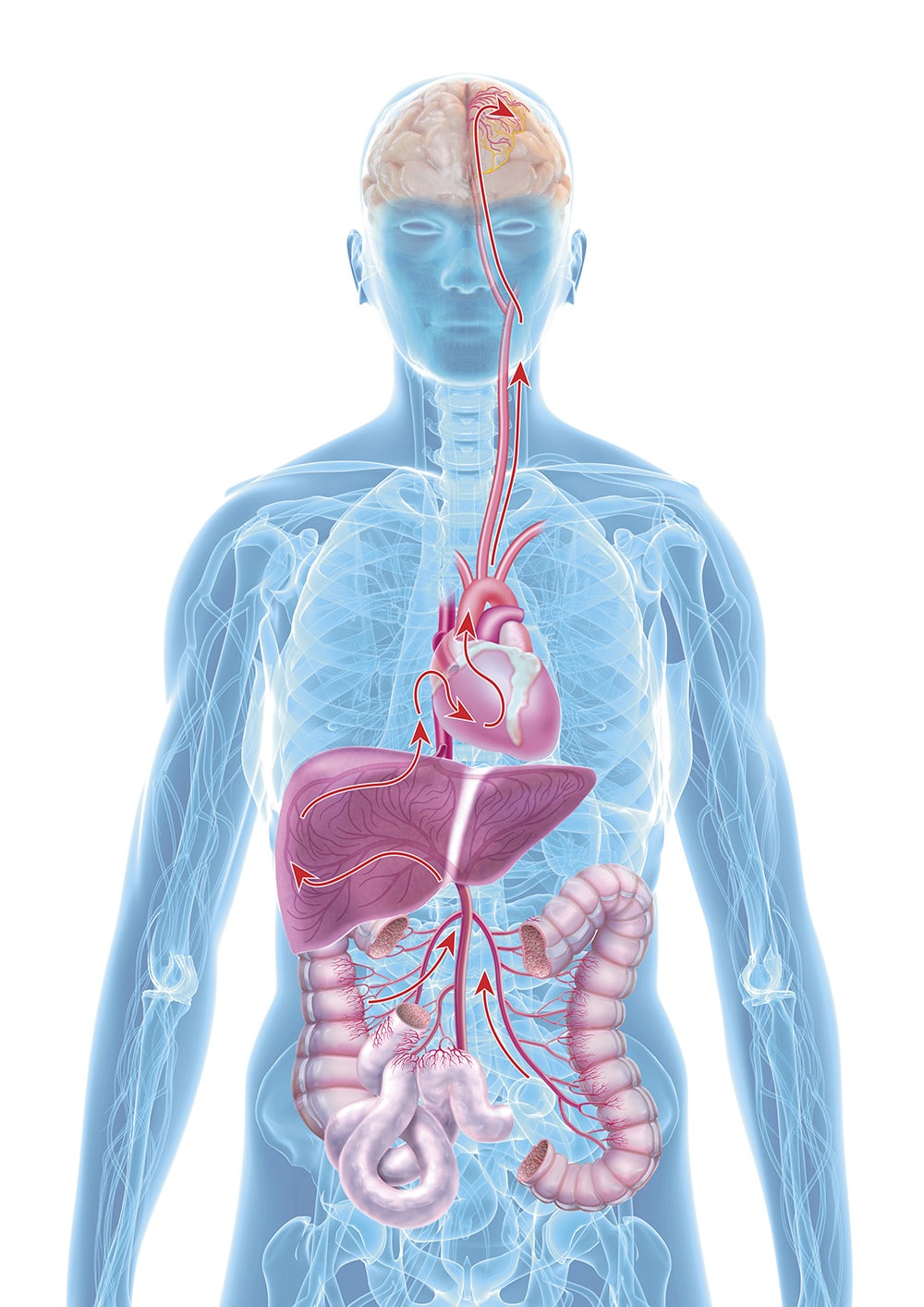

That sounds complicated, and ultimately it is. However, medicine has known for a long time about the significance of "silent" infections for the occurrence of diseases. In 1999, for example, it was shown that the same inflammatory substances are present in the blood clot that first blocks a coronary vessel and then leads to a heart attack as in a joint with rheumatic inflammation. Research over the last ten years has now brought a new factor into play. Namely, the damaged intestine ("leaky gut"), with changes in the gut flora and damaged epithelial cells, and its effects via the gut-brain axis.

"Leaky gut" means, in medical terms, an "imbalanced intestinal barrier". When the mucous membranes of the intestinal tract become permeable due to inflammation, harmful substances can enter the entire body via the bloodstream, including the central nervous system (CNS) and therefore the brain. The term "leaky gut syndrome" was first mentioned in a publication in the 1990s, but at that time it was mainly a topic in complementary and alternative medicine. This has changed fundamentally in the meantime. Associations of a damaged intestinal barrier with various diseases are now also considered highly probable by orthodox medicine, ranging from obesity and diabetes to dementia, coeliac disease, and liver damage.

Prof. Leblhuber explains the possible effects of an immune deficiency on the central nervous system: "A leaky gut is caused by local inflammatory processes. The transfer of inflammatory cells into the bloodstream then also causes chronic infections in other, peripheral regions of the body. The inflammatory cascade is likely to finally end via the autonomic nervous system with central neuroinflammation in the brain, which is one of the early, detectable changes in patients with Alzheimer's dementia. This process could begin decades before the first symptoms appear. The starting point for this is ultimately the leaky gut, which we can track down by analysing certain parameters such as increased concentrations of calprotectin in the stool. A Swedish research group clearly postulates that, according to their studies, the development of Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases originates from the microbiome."

"When the intestinal barrier is imbalanced (leaky gut), bacteria and their metabolites can move from the intestine to other parts of the body and do damage elsewhere."

Probiotic intervention

Prof. Leblhuber also believes that therapy with anti-inflammatory probiotic bacteria can have a massive influence on the inflammatory process. Confirming results are now available from animal experiments as well as from his own studies with patients. Namely, the gene expression in the cerebral cortex can be changed and inflammation reduced by administering probiotics. Since changes in the microbiome and inflammation-related damage occur very early in the course of a neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer's, probiotic therapy as early as possible could have a beneficial effect. This assumption, which is now widespread among experts, is currently being researched in more detail in further studies. "If it is possible to stop the local inflammation through probiotic intervention in the intestine - which we assume," says Prof. Leblhuber, "then protection against degenerative processes in the brain, which underlie Alzheimer's dementia, should also result from this."

It would even be possible to improve neurodegenerative changes that have already occurred by using synbiotics that specifically reduce inflammation and strengthen the intestinal barrier.

Our Gut over Time

Our gut is still often not given the attention it deserves - and wrongly so! The intestine is not only our largest organ, but with its trillions of intestinal bacteria, it is also centrally responsible for our health and well-being.