Margit Koudelka

Our intestines during a lifetime

Our intestines often and unfairly don’t receive the recognition they deserve: The intestines aren’t only our biggest organ but are also centrally responsible for our health and well-being with its trillions of gut bacteria.

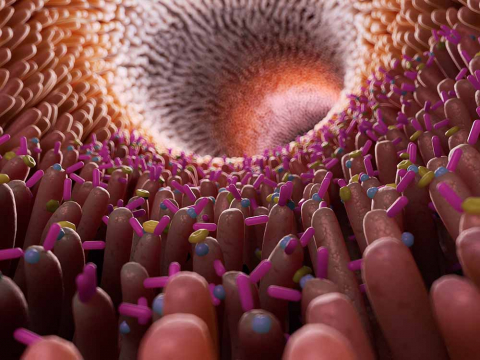

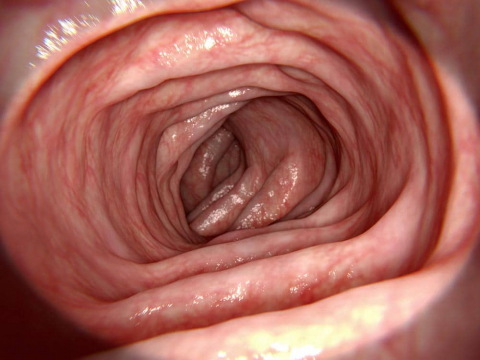

It’s almost impossible to imagine: The intestines can be up 8 metres long but only a few centimetres wide and form the connection between the stomach and the anus. Within this coiled, muscular tube, we can find the so-called intestinal villi with millions of protrusions that increase the surface area of the bowels. If we stretched out our digestive tract, it would cover approximately 300 square metres.

During the course of a 75-year life, about 30 tonnes of food and 50.000 litres of liquid pass through our gut, as well as countless pathogenic germs and toxic substances. The digestion is partially controlled by our enteric nervous system (ENS), also known as the „gut brain“: About 100 million nerve cells can be found in the wall of the intestines and form an independent part of the nervous system. The ENS controls the intestinal motility (in other words, the contraction of the muscles in the intestines) and therefore the transportation of food. The ENS also affects the immunological function of the intestine, influences the transport of ions and is also in charge of the blood flow in the digestive tract.

The trillions of helpful bacteria that inhabit our intestines, however, have a much larger impact on our digestion: They produce enzymes that break down food and therefore make it digestible for our bodies, supply us with energy by producing short-chained fatty acids, produce vitamins (i.e. vitamin B2, B12, K, folic acid and biotin), neutralise toxic substances and help maintain a functional immune system – the intestine is an outright „health centre“.

The importance of chewing properly

Every meal that we eat begins a 48-hour journey through our digestive tract from the moment we first take a bite. The first steps of digestion already start in our mouths: by chewing, we grind the food and mix it with our saliva. The enzymes within our saliva already start breaking down carbohydrates. The food is then transported via the oesophagus into the stomach. Easy to digest food, such as fruit and vegetables, stay here for about 1-2 hours whereas heavy, fatty foods can stay up to 8 hours. With the help of gastric acid, large pieces of food are converted into a bolus which is then passed on to the small intestines – this is where the main part of the digestion takes place. Within the first section of the small intestines, the duodenum, the acidic food bolus is neutralised, among others, by the secretions of the pancreas so that the digestive enzymes have the optimal surroundings to work in.

Millions of intestinal villi increase the surface area of the intestines.

Their job is to break down food into its individual components (i.e. carbohydrates, protein, fats, minerals, trace elements, vitamins and water) within the entire small intestines and therefore make it digestible for our bodies. The nutrients within our food are then absorbed by the intestinal villi and distributed within our organism via the bloodstream. The intestinal bacteria draw their energy from dietary fibre so that they themselves can produce vitamins as well as short-chained fatty acids as a source of energy or immuno substances. Afterwards, the food bolus enters the large intestines. Here, water is removed from the indigestible part of the drastically altered food, and a slime (mucus) produced by the intestinal cells is added. In this manner, the food bolus is thickened.

The afflictions of the intestines

Many factors can disturb the normal function of the intestines: The intake of drugs such as antibiotics, an unbalanced diet, a lack of exercise and infections. Even stress and hereditary factors can have a negative effect on the intestinal flora and the function of the intestinal barrier. Diarrhoea, i.e. more than 3 watery bowel movements per day, is one of the most common signs that the intestine isn’t functioning properly. By increasing the frequency of bowel movements and intensifying the expulsion of water out of the intestinal cells, the body tries to get rid of harmful substances such as germs or toxins.

If these unwanted components of our food stay too long in our bodies, they can cause damage throughout the entire organism. This can happen in the case of constipation, only 3 or fewer hard bowel movements per week. Diarrhoea, as well as constipation, usually aren’t serious – as long as they only occur sporadically and don’t involve other symptoms – and can be attributed to food intolerances for example. However, a dysfunctional digestion can also have serious causes or severe consequences and should be consulted by your doctor if the symptoms are prolonged.

The intestine, the defensive specialist.

About 80% of the defence cells of our immune system can be found in the intestines, especially in the mucosa of the large intestine. They are responsible for rendering toxins and other pathogenic germs harmless. These defence cells are supported by billions of helpful bacteria from several hundred different species which make up our intestinal flora, also known as the microbiome. These helpful inhabitants in total „only“ weigh in at about 2kg but definitely have a “heavy” impact: A balanced composition of these microscopically small intestinal inhabitants make sure that other microorganisms can’t permanently settle down in our intestines. These healthy gut bacteria produce many important immune components and hormones. As a result, our microbiome doesn’t only play a key role in our intestinal health, but rather for our entire well-being.

A changing microbiome

Scientists thought, for a long time, that the digestive tracts of unborn infants were sterile, or in other words, free of bacteria. By now, researchers have found several clues that the baby’s intestine is already colonised by healthy bacteria before birth. In a study from 2014, scientists extracted microbial probes from 320 placentas directly after birth. Using modern techniques, the presence of bacteria, that was similar to that of the mother, was found in the placenta. This again offers further clues that bacteria can be passed on from the mother to her child during pregnancy.

Even the birthing process can determine the composition of the intestinal flora in a child. During a vaginal birth, the mother passes her bacterial flora on to her baby – whereas this contact with the vaginal flora of the mother is completely missing during a C-section. In the case of the latter birthing process, the child’s intestinal flora is mainly comprised of the skin bacteria of the mother as well as microorganisms from the hospital’s surroundings and leads to a microbiome largely made up of atypical bacteria. These babies often suffer from allergies and other diseases. Whether a child receives breastfeeding or bottle feeding can also influence the composition of the microflora. The intestines of breastfed children contain a large number of bifidobacteria which efficiently defend the body against pathogenic germs.

Clinical studies also show that probiotics, during pregnancy and from birth onwards, can have a positive influence on a child’s immune system: The intake of selected helpful intestinal bacteria significantly lowers the risk of developing allergies such as asthma or neurodermatitis.

Is it all a matter of type?

During the course of a human life, an increasing number of different bacteria settle down in our intestines. Many different factors determine which bacteria settle down and how they are comprised, and vary widely depending on the genetic preconditions, diet and lifestyle. There are 3 different types of bacteria (enterotypes) that inhabit our intestines: We distinguish between Bacteroidetes, Prevotella and Reminococcus depending on which type of bacteria dominates the intestines. Our food is digested differently depending on the predominant type of microorganisms.

- Enterotype 1 – Bacteroidetes-dominant type: These bacteria are associated with a diet rich in proteins and saturated fats.

- Enterotype 2 – Provetella-dominant type: This species is mainly found in people with a carbohydrate-rich diet.

- Enterotype 3 – Ruminococcus-dominant type: Such microorganisms are involved in breaking down sugars and mucins.

The above-mentioned enterotypes can help determine the tendency towards certain diseases.

The majority of our gut bacteria inhabit the large intestines. Furthermore, about 80% of our immune cells can be found in the mucosa of the colon.

Decline in variety

For women, the menopause brings about many physical changes. Due to the hormonal changes, not only the intestinal flora but also the vaginal flora is altered. The number of lactic acid bacteria decreases which can lead to complaints around the genital area. Probiotics can help here as well: helpful lactic acid bacteria settle down in the vagina and oust harmful germs such as Candida albicans or Gardnerella vaginalis. These bacteria can even be taken orally: The anus serves, so to speak, as a reservoir for the vaginal flora – helpful microorganisms reach their destination via the mucosa between the anus and the genital area.

The diversity of species in the intestines decreases significantly in old age and is caused by a change in lifestyle: Older people tend to have a one-sided diet, move less, suffer from more infectious diseases and take more medications, all of which have a negative impact on the intestinal flora. This results in a reduction of the healthy intestinal flora and an increased colonisation with rot pathogens. That is why it isn’t only important but also necessary with age to have a diverse diet, enough exercise, avoid stress and take as little medications as possible. Probiotics with carefully selected and medically relevant bacteria species rebuild the biodiversity of the intestines and maintain the „health centre“ in the intestines for a long time to come.