Mag. pharm. Eva Owesny and Emanuel Munkhambwa

Gut bacteria in profile

Dr. Jessica Younes (PhD), probiotic scientist in Amsterdam

As the result of an unhealthy diet, different medications and even stress, the harmonious cooperation between our intestinal bacteria can become unbalanced. And precisely these changes can lead to the „bad“ bacteria spreading out and replacing the „good“ and „helpful“ bacteria. But which bacteria are important for our bodies and which can cause diseases?

The „Good“ and the „Bad“ gut bacteria

Dr Jessica Younes (PhD), a probiotic scientist in Amsterdam, believes the following: The more we know and learn about the „good“ bacteria, the better we can improve our health. „These „good“ intestinal inhabitants help with digestion, produce vitamins and even hormones“, explains Dr Younes. For example, the bacteria species Bacteroides, from the family of the Bacteroidetes, play an important role in the biosynthesis of the vitamin Biotin. Biotin is, among others, important for our energy metabolism, the nervous system, our minds as well as our skin, hair and mucosa.

The Prevotella species, also from the Bacteroidetes family, produces a lot of vitamin B1 (Thiamine) which is essential for our energy metabolism, nervous system, mind and even cardiac function. But what makes some bacteria „bad“?

„Even nowadays, scientists are unsure as to why some bacteria from the same species (for example E. coli) cause problems in our intestines and others don’t. If the bacterial flora is unbalanced, „bad“ and pathogenic bacteria can proliferate and therefore replace the „healthy, good“ bacteria. Consequently, the digestion and absorption of nutrients is disrupted”, clarifies Dr Younes. If we take a closer look at the variety of intestinal bacteria, we recognise that the majority of these small inhabitants are very useful for our digestion and health. Some of the bacteria maintain a low profile, don’t have special tasks and live in peaceful coexistence.

The more we know and learn about the „good“ bacteria, the better we can improve our health.

Clostridium difficile

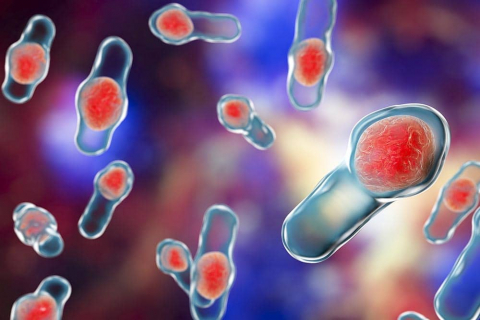

However, a third group of bacteria can cause problems under certain circumstances by „infecting“ the intestinal mucosa and triggering, among others, diarrhoea. This „infection“ can either be caused by foreign bacteria or by bacteria that usually live peacefully in our intestines and only cause problems when the balance in our bowels is disturbed, for example after an antibiotic treatment. The bacterium Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) is usually not found in high numbers in our intestines and doesn’t cause any problems. Most importantly, this species is kept in check by the other „good“ bacteria. After treatment with antibiotics, however, the bacteria that control C. difficile are decimated, and the „bad“ germs reproduce rapidly once the intake of the antibiotics has ceded. They can cause severe damage in the intestines as C. difficile produces different toxins.

Clostridium difficile causes 15-20% of antibiotic-associated diarrhoeas and is responsible for more than 95% of all pseudomembranous colitis cases. Out of 100 people that were treated with antibiotics, we can expect 1 person to have an infection with C. difficile.

The so-called Toxin A causes inflammations in the intestines and can lead to an increased secretion of liquids (= runny stool or diarrhoea). Even more dangerous, however, is the Toxin B, as it destroys the cells in the intestinal mucosa on a large scale. In many cases, a C. difficile infection doesn’t just stop with diarrhoea. Often enough, an inflammation of the intestines can develop, a so-called pseudomembranous colitis. Despite meticulous hygienic measures, C. difficile infections can’t be prevented as this germ multiplies through sporulation – and these spores are resistant towards disinfectants, heat, acids and alcohol.

For this very reason, it is extremely important to support the intestines with specially developed probiotics during and after antibiotic treatment. The probiotics help against the diarrhoea caused by the antibiotics and, more importantly, counteract the toxic substances of C. difficile that trigger the diarrhoea.

Probiotics on the rise

Scientists can all agree that it is crucial to keep the intestinal microbiome in good health. More specifically, so that the „good“ bacteria are strong enough to fight against the bad germs and keep them at bay. The indigenous bacteria of the colon produce short-chain fatty acids out of ingested carbohydrates, such as lactic acid, acetic acid and butyric acid. These acids all serve as a vital source of energy for the intestinal mucosa cells, reduce inflammation and promote peristalsis, i.e. digestion. The idea of positively influencing the intestinal flora „from the outside“, in other words through food, emerged at the beginning of the last century.

The „good“ germs in the intestines can multiply when surrounded by a suitable source of food, the perfect job for prebiotics.

The Russian scientist Ilja Iljitsch Metschnikoff (1845-1916) traced the old age of the Bulgarian population back to their eating habits. Among others, a lot of yoghurts and other acidified or fermented dishes were a part of their menu. Back then, people already assumed that a regular intake of lactic acid producing bacteria (Bulgarian Bacillus) had a positive effect on general health. In 1908, Ilja Iljitsch Metschnikoff received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work on immunity. However, this was still a long way off from recognising the positive effect of probiotic foods and especially „healthy“ gut bacteria in scientific circles. Living bacteria that can be found in lactic products such as yoghurt, buttermilk or even sauerkraut are referred to as being „probiotic“. These living bacterial cultures, mainly lactobacilli and bifidobacteria, are added to food products in order to ferment them and have a health-promoting effect.

Dr Younes emphasises that every probiotic bacterium has its own special ability: „Some produce large amounts of lactic acid or vitamins in the intestines, while others prevent bad bacteria from proliferating or boost the immune system. Lactic acid regulates bowel movements and changes the pH-value in the intestines so that pathogenic bacteria can’t multiply. As a result, probiotics can also be used against diarrhoea as well as constipation.“ However, to achieve a good effect, probiotic bacteria need to reach the intestines alive and in large numbers. The intake of standardised, scientifically proven bacteria preparations (available at your local pharmacy) with especially robust bacterial strains is recommended. These bacteria are able to withstand the attack of the digestive juices in the gastrointestinal tract and can then colonise the intestines.

Bacteria need the „right“ food.

The „good“ germs in the intestines can multiply when surrounded by a suitable source of food, the perfect job for prebiotics. They make sure that the small inhabitants feel well, can multiply and therefore allow them to regulate the digestion. Prebiotics, in particular, support the growth of „good“ gut bacteria. Eating plenty of fibre-rich foods with a natural dose of prebiotics gives the intestines the perfect kick-start. Prebiotics can be found especially in bulbous plants, black salsifies, artichokes, asparagus, chicory, rye, wheat, oats, bananas and apples.

Other important factors include resistant starch, galactosaccharides and fructooligosaccharides which are broken down into short-chain fatty-acids by the bacteria in the intestines. By the way, these short-chain fatty-acids play an important role in a completely different part of our body: Butyrate isn’t only vital as an energy source for the intestinal wall, but also an essential nutrient for the so-called microglia-cells. These are the immune cells of our brain that act, so to speak, as the „garbage disposal“ of brains and remove toxic substances from our „control centre“. If our intestines are in top gear, then so is our brain – our thinking as well as our emotions.

Dr Younes points out that taking probiotics and prebiotics as well as fibres at the same time makes sense because they complete each other: „Prebiotics are the perfect food source for intestinal bacteria and stimulate the growth of „good bacteria“. Our intestines can’t digest the fibres, but the bacteria can break them down and produce other substances that are beneficial for our health. One of the best examples of the perfect combination between pre- and probiotics is breastmilk.

Lactobacilli create an acidic environment within the intestines and the female vaginal area by fermenting carbohydrates to lactic acid. As a result, the growth of pathogenic germs is inhibited.

A breastfed child receives „good“ bacteria and galactooligosaccharides via the breastmilk and is ideal for the baby’s development“.

Our intestines and, more particularly, the intestinal bacteria that are found within are essential for our health – if the normal function of the intestines is disturbed due to a loss of its inhabitants, then it is also responsible for the development of many diseases. The following has been known for millennia: „The intestines have the same importance for humans as the roots for a tree“. We should remember this wisdom and take care of our health centre so that it can take care of us.

Helpful gut bacteria

Lactobacilli

They belong to the family of the Firmicutes; a term that originates from the Latin word lactis (=milk). More than 50 known species produce lactic acid in the intestines and therefore create an acidic environment that protects us from harmful and pathogenic germs – hence the name lactic acid bacteria. Most lactic acid bacteria produce other substances, such as hydrogen peroxide, which also acts as a defence against pathogens.

Bifidobacteria

These belong to the family of the Actinobacteria; a term that derives from the Latin word bifidus (= divided, forked). They also protect us from unwanted intruders by producing lactic acid. What’s more, they produce vital vitamins and enzymes. They are especially important for the infantile development of the immune system: The natural intestinal flora of a breastfed infant is made up of about 90% bifidobacteria.

Pathogenic germs

Clostridium difficile

A species of bacteria belonging to the Firmicutes; named after the Greek word kloster (= spindle) and the Latin word difficile (= difficult). C. difficile can mainly be found in hospitals, about 20-40% of hospital patients are inhabited by this germ. When C. difficile overwhelms the intestines, it often leads to severe diarrhoea and a massive inflammation in the bowels.

Staphylococci

From the Firmicute species, and the Old Greek word staphyle – (= grape) and kokkus (= corn, seed). Staphylococci can be the cause of many different types of infections and lead to entirely different symptoms. Besides skin irritations, these bacteria often cause food poisoning with symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, emesis, stomach cramps or diarrhoea. The worst-case scenario is when these bacteria enter the bloodstream and then wreak havoc. This is then known as blood poisoning or sepsis.

During an acute inflammation of the renal pelvis, flank pain, fever, as well as nausea and vomiting, predominantly occur.