Heidrun Valencak

Cancer, chemotherapy and the microbiome

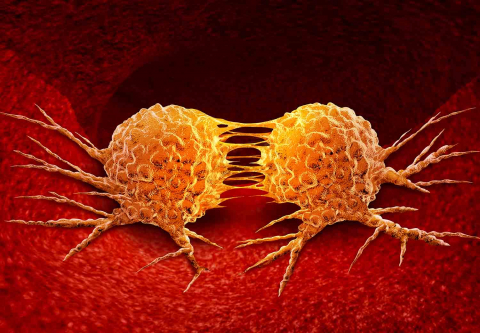

Cancer is a central health issue in our modern society: The number of new cases and the risk of mortality may be in a downward trend, but cancer is still one of the most common causes of death and could affect 4,9% of all Austrians by the year 2030 due to the society’s ageing population. Mag. Anita Frauwallner discusses with Prof. Christoph Castellani how tumour diseases change the microbiome and what influence pro- and prebiotics could have as an add-on therapy.

Ass.-Prof. PD Dr. med. univ. Christoph Castellani*

Mag. Anita Frauwallner:Cancer is affecting more and more people worldwide so that almost every single person comes into contact with it in one way or another. You focus on metabolic disorders that arise in cancer patients – both in children and in adults – in your research and study its connection with the intestinal bacteria. What microbial function is especially relevant for cancer patients?

Prof. Christoph Castellani: Our microbiome can have an influence on our health in many different ways. For example, indigestible carbohydrates are broken down into short-chain fatty acids (SCFA’s) by the intestinal bacteria. These SCFA’s reduce inflammations in the body, strengthen the intestinal barrier and are an important source of energy for the epithelial cells, the innermost layer of our intestines.

However, when bacteria disintegrate, they can release toxins that cause severe inflammations which may then damage the intestinal wall. This is one of the most important barriers in our body as it prevents harmful substances from being absorbed. At the same time, the intestinal wall allows water and nutrients to pass through and become available for our organism. So that this selective barrier can work, it is vital that the epithelial cells are closely linked: They are glued together by so-called Tight Junctions, and a healthy bowel can precisely open and close these connections to allow nutrients to pass and „reject“ pathogens.

When the intestines enter a state of dysbiosis, in other words, a change in the intestinal flora composition, it has a negative impact on our health due to a lack of short-chain fatty acids. As a result, the cells in the intestinal wall are under-nourished, and the intestinal barrier is damaged. This is how bacterial toxins and other harmful substances in our food can enter our bodies via the intestinal wall. These then activate immune cells and cause an inflammatory response. Thus, a vicious cycle develops: The intestinal wall becomes leaky due to the inflammation, the leaky intestinal wall then amplifies the inflammation and ultimately, the amplified inflammation makes the intestinal wall even more permeable.

Mag. Anita Frauwallner: We already know that patients with different inflammatory diseases such as dementia, multiple sclerosis and liver diseases have an altered microbiome. Is this also the case in cancer patients? Or is an altered intestinal flora even responsible for the development of cancer?

Prof. Christoph Castellani: It is certainly possible that a state of dysbiosis could be one of the factors that lead to tumour development: The composition of the microbiome changes, pathogenic germs produce toxins which provoke intestinal cancer. These harmful changes to the intestinal bacteria are a result of the intake of medications and, especially, a poor diet: Our usual diet including generous portions of meat, fast food, soft drinks and sugar is bad for our microbiome. What’s more, we also ingest cancerogenic substances (e.g. alcohol; heavy metals; cadmium from cigarette smoke) through our food.

Studies show how damaging our diet is by investigating the effect that our food has on the development of intestinal cancer: The consumption of red meat, sausage and ham products, as well as alcohol, are considered as being particularly cancerogenic – and even obesity, which affects 55% of all Europeans, plays a central role. Animal fats, cheese and sugar also seem to induce the development of colon cancer.

We also know that patients with intestinal cancer have a noticeable decrease in lactobacilli, or lactic acid bacteria, and faecalibacteria, which are important manufacturers of SCFA’s. There is, conclusively, a definite correlation between the microbiome and tumours.

Mag. Anita Frauwallner:One of your areas of research focusses on the so-called cachexia in cancer. What is that exactly? Is there any correlation to the microbiome that can be confirmed by studies?

Prof. Christoph Castellani: Cachexia is a type of deficiency defined by the loss of fat and muscles. It predominantly occurs in cancer patients: About 50% of adults with malignant tumours – in some instances only temporary – have to deal with this emaciation. Cachexia is even the cause of death in 20-50% of cancer patients. The problem is that, not only do the patients lose fat and muscle due to various metabolic diseases, they also suffer from a lack of appetite: They’re not hungry anymore. This missing sense of hunger is partly due to the side effects of chemotherapy but also directly the result of the cachexia. This affliction leads to a reduced sensation of hunger by causing inflammations and modulation of the brain. This can also be seen in children, where 46% of these small patients with neoplastic diseases show tumour-related malnutrition.

Because of the cachexia, the patients are not only weakened, they are also more susceptible to infections and have a delayed wound healing – which is particularly unfavourable after surgery. The efficacy of chemotherapy is reduced which also has a negative result on the patients‘ prognosis.

Our goal in cancer therapy should be to preserve the patient’s microbiome in order to perform effective chemotherapy.

We even conducted 2 experimental studies: In both models, the mice suffering from cancer developed cachexia, lost fat and muscle mass, and we could clearly see that several lactobacilli species were significantly reduced in the mice’s stool. Apparently, cachexia changes the microbiome, most noticeably through the reduction of lactic acid bacteria.

Mag. Anita Frauwallner: You just mentioned that chemotherapeutics – which are undoubtedly necessary – also have a negative impact on the microbiome. Are there any side effects that could drastically reduce the course of treatment?

Prof. Christoph Castellani: Chemotherapy is used to destroy cancer. One of the side effects of this treatment is the increased intestinal permeability: Chemotherapeutics are made to attack cells that multiply quickly. These include cancer cells, but also hair follicles (which explains the loss of hair in cancer patients) and the cells in the intestinal mucosa. The permeability of the intestine is increased due to a change in the Tight Junctions and the destruction of epithelial cells. As a consequence, and as mentioned earlier, more bacterial toxins enter the body and aggravate any prior inflammation.

The most severe side effect of chemotherapy, however, is mucositis: An inflammation of the mucosa throughout the entire digestive tract, accompanied by stomach-aches, nausea, emesis, (bloody) diarrhoea or constipation. These are very common complaints that occur in 40% of adults and even 60% of children. The big problem is again the intestinal permeability which allows bacterial toxins to enter the body and cause deadly infections. What’s even worse is that we have to reduce the chemotherapy dosage because of the mucositis – which, in turn, reduces the efficacy of the chemotherapy. In other words, our intestines force us to use a less effective treatment. When it comes to the microbiome, the mere administration of chemotherapeutics leads to a state of dysbiosis in the intestines.

Furthermore, test groups show that animals with cancer generally have fewer bacteria in their intestines than healthy ones. The combination of cancer and chemotherapeutics is especially severe for our intestines – with the important lactobacilli being affected the most. However, we know from a recent study that an intact, healthy microbiome is essential for the function of chemotherapy. That is why our goal in cancer therapy should be to preserve the patient’s microbiome in order to perform effective chemotherapy.

Mag. Anita Frauwallner: We know from our research at the AllergoSan Institute that pre- and probiotics play an essential role in maintaining our intestinal health. Have you made any experiences with this in chemotherapy and the treatment of cancer?

Mag. Anita Frauwallner: We know from our research at the AllergoSan Institute that pre- and probiotics play an essential role in maintaining our intestinal health. Have you made any experiences with this in chemotherapy and the treatment of cancer?

Prof. Christoph Castellani: We know from study data that higher consumption of natural fibres, e.g. pectin, inulin and maltodextrin, reduce the risk of bowel cancer. Just changing from a western diet to a fibre-rich food can make all the difference. The benefits of a targeted combination of pre- and probiotic dietary supplements are even more profound: Prebiotics, a.k.a. fibres, support the resident bacteria and transport the bolus through the digestive tract more quickly.Therefore, we are only exposed to these cancerogenic substances for a short period. Furthermore, experimental studies show that, for example, inulin promotes the growth of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria. As a result, more short-chain fatty acids are available, and inflammation markers are reduced. The intake of pectin even reduced the loss of fat, lipolysis, and increased the feeling of hunger.

Probiotics have many different positive effects: They prevent the adhesion of pathogenic germs in the intestines by changing the pH-value in favour of the helpful bacteria and stimulating the immune system. This has also been successfully shown in experimental studies: After the administration of lactobacilli, inflammatory markers and muscular atrophy were reduced. The combination of pre- and probiotics could have a positive impact on cachexia and therefore form an important add-on treatment.

There is positive, straightforward data concerning the use of probiotics to reduce mucositis. Many studies – the largest including almost 500 patients – indicate that the use of probiotics could significantly reduce mucositis and chemotherapy-associated diarrhoea in adults as well as children. Probiotics are therefore an important adjunctive treatment during chemotherapy to reduce severe side effects and enable effective treatment.

Mag. Anita Frauwallner: Thank you so much for the conversation – we look forward to seeing new research findings!

*Ass.-Prof. PD Dr. med. univ. Christoph Castellani is a specialist in Paediatric Surgery at the Medical University Graz. His research focusses on inflammations, disorders of the intestinal wall barrier and metabolic disorders involved in cancer, all of which originate from the microbiome.